In conversation with Samuel Gikonyo, Fund Management Lead, Crown Agents

Born in a village located in Central Highlands of Kenya, I left with my father for the city at the age of four, and grew up in one of Nairobi’s informal settlements - the Laini Saba village in Kibera.

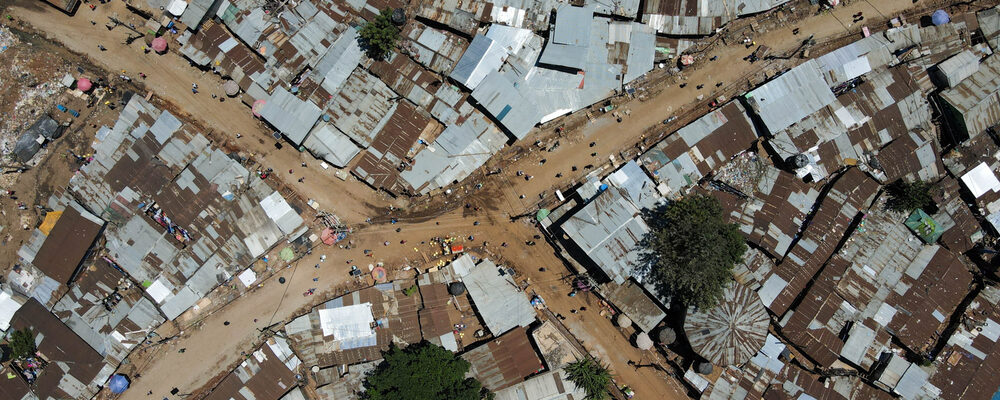

Kibera is 6.6 kilometres from the city centre and the largest informal settlement in Africa, with a population that may now be well over 1,000,000 people.

Informal settlements are at particularly high risk from the impacts of climate change and natural hazards. Living on the least desirable lands, the residents are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of flooding, for example.[1] [1] It is important to note that informal settlements are home to up to 60% of city dwellers in many low- and middle-income countries.[2]

As a result of my environment, I developed an interest in climate from a very early age. Adverse weather events impacted my life quite substantially whilst I was residing in Kibera: During Kenya’s rainy season, for example, our accommodation was often compromised, as its structure was not solid. Mud houses can be swept away by the rain, but also, the rain would carry away our belongings, including food we had prepared for the next day. I remember standing on the bed one night and watching our household items being swept away, and I would ask myself where these heavy rains were coming from. As a result, I developed an unsatiable appetite to read, including newspapers and magazines, even before I entered secondary school. Later in my educational journey, I wrote about climate change myself, including the impact of Kenyan farming practices on the Ozone layer.

Whilst informal settlements do help with access to economic opportunities in the city- my father soon found work as a security and construction worker- we did struggle with a variety of other infrastructure challenges- not only because our houses could sometimes not withstand the heavy rains, but also because homes in the settlement were not connected to water or sewerage networks. There was water which could be accessed from containers, but you could only shower once a week in an open area of the settlement built for this purpose. Because so many people were relying on it, we could only use it one day per week. On the other days, I would just wash my face and legs and go to school.

Given these challenges, residents often resorted to unsustainable coping strategies to ensure access to water, such as drilling boreholes into aquifers, or repositioning public water pipes. This results in the overexploitation of natural resources, which is not sustainable- urgent solutions for basic service provision are needed in these environments.

Another challenge I noticed whilst growing up in Kibera was around waste disposal, especially that of plastics, which were lying around in abundance. It did not help that waste disposal was not organised in any way- people just put it in a whole in the ground and waited for the waste to be swept away by the heavy rainfalls. However, this would at times cause blockages in narrow streets, causing flash flooding, posing additional challenges.[3]

The journey: From managing a shop in an informal settlement to leading on water sanitation projects for PwC

Spending as much time in this environment as I did, I wanted to make money, and above all with the skills I had and enjoyed. After 10 years of working in the city, my father had enough funds to start a shop. It was there where I developed an interest in accounting I could then apply to my subsequent education and career. I had started to appreciate money and what it can do. I loved counting and managing funds, which is why I went into accounting in the first place, and later worked for Deloitte in auditing.

However, the desire to effect change for others never left me. This is why I joined PwC, where my first projects were in agriculture and water sanitation. I loved seeing the change being implemented on the ground, and not just looking at the numbers.

Nevertheless, the urge to work for an organisation like Crown Agents always stayed with me. From my new office at Crown Agents in Kenya, I can in fact see my primary school on the opposite side, and this reminds me how far I have come, and what I still would like to achieve for my people and our community globally.

In my fund management consultancy position at Crown Agents, I assess where Crown Agents’ expertise in managing and dispersing funds to local organisations is best applied and can achieve the most impact. I lead on our global strategy and dedicate my time to spotting opportunities to apply this expertise, with the aim to truly leaving no one behind.

Climate finance: A call to focus on the most vulnerable, especially in urban settings

Major climate financing often overlooks the upgrading of informal settlements to increase local resilience. Yet, creating jobs by financing sustainable local infrastructure does not only lift people out of poverty, but offsets future climate related costs and discourage residents use other, less sustainable strategies to obtain access to water, energy and food.[4] And last but not least, it will save lives- because climate change is associated with more extreme precipitation events and rising sea-levels, African cities will experience more severe and more frequent flooding in the future.[5] It is up to local governments to ensure the necessary funding is mobilise and allocated- and once it is, we must ensure maximum impact- something I hope that we, at Crown Agents, can help do.

About Samuel

Based in the Crown Agents Kenya Office, Samuel Gikonyo leads Crown Agents’ global fund management strategy.

He is a highly experienced leader of programmes, skilled in managing relationships with senior government and development partners stakeholders, and a trusted partner in overseeing strategic grants/projects implementation. As a smallholder tea farmer, and following his childhood in Kibera – the largest informal settlement in the world, Samuel has first-hand experience of the impact of climate shocks and the vulnerability of the poorest communities. He is passionate about strengthening government capacity to effect climate transitions in Kenya and has supported the Ministry of Agriculture’s sectoral support programme and the national agriculture and livestock extension programme that was implemented over 60 districts of Kenya – both improving government systems to improve livelihoods and food security, employment and competitiveness in the sector.

He is a highly experienced leader of programmes, skilled in managing relationships with senior government and development partners stakeholders, and a trusted partner in overseeing strategic grants/projects implementation. As a smallholder tea farmer, and following his childhood in Kibera – the largest informal settlement in the world, Samuel has first-hand experience of the impact of climate shocks and the vulnerability of the poorest communities. He is passionate about strengthening government capacity to effect climate transitions in Kenya and has supported the Ministry of Agriculture’s sectoral support programme and the national agriculture and livestock extension programme that was implemented over 60 districts of Kenya – both improving government systems to improve livelihoods and food security, employment and competitiveness in the sector.

As Senior Manager at PwC Kenya responsible for managing and supervising execution of clients’ programme management, risk management and fund assignments. Samuel was also deputy head of advisory department at PwC Malawi, responsible for up to 4000 long term and short-term staff. In this role he was responsible for business development, fund management, key stakeholders’ management, staff coaching and risk management. As a member of the PwC Environment Social and Government group, Samuel worked on concept design for projects with the Green Climate Fund, Sustainable Financing in Kenya and supported an EU concept for 10 counties in Kenya on WASH and waste management.

Having transitioned from one way of life to another, he admits that I do sometimes miss the hard, physical work- carrying water, the early walks to primary school. This is why Samuel has a passion for body-building- a great outlet for his physical energy.

Sources:

[1] https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-0-8213-8845-7

[2] https://www.iied.org/health-wellbeing-climate-benefits-slum-upgrading

[3] https://earlychildhoodmatters.online/2021/climate-change-is-forcing-young-children-into-high-risk-urban-slums/

[4] https://www.citiesalliance.org/newsroom/news/spotlight/climate-change-and-urban-poverty-why-we-should-care