By Lieut. Gen. Louis Lillywhite, Oriole Global Health advisor

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK-Aid funded Ascend (Accelerating the Sustainable Control and Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases) programme was in a central position in the countries it works in to provide support and input to key national task forces set up to directly review and address the emerging outbreak.

This is because Ascend operates with an emphasis on partnership and government ownership. It is a partnership with ministries of health (MoH), working through country representatives and supported by Ascend’s global leadership, programme support and technical teams.

These existing partnerships meant the programme was ready to pivot existing funding to assist governments with retargeted priority outbreak support activities, and as part of a secondary response, it was able to develop and adopt a suite of tools to support later implementation of NTD programmes in a safe and effective manner.

Ascend is a programme targeting five neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) — lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, trachoma and visceral leishmaniasis — funded by the UK Foreign commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and delivered by a consortium of partners including Crown Agents; Abt Associates; KIT the Royal Tropical Institute and Oriole Global Health.

The programme works in Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Nepal and Bangladesh.

Following several months of implementation of both retargeted activities and NTD implementation, Ascend lot 1 held two roundtable learning events to gather and share information from Africa and Asia country leads.

Below are the main themes that emerged.

-

Initial COVID-19 outbreak responses and the challenge of reinstating NTD services

East African countries initiated an early response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the introduction of a range of measures coordinated by distinctive emergency task forces. These included school closures, targeted behaviour change and communication (BCC) campaigns, mask-wearing mandates and national or regional lockdowns.

Given initial experiences in China and Italy, the expectation of a very high mortality rate justified the World Health Organization’s (WHO) early advice to national governments to suspend most components of neglected tropical disease (NTD) programmes [1].

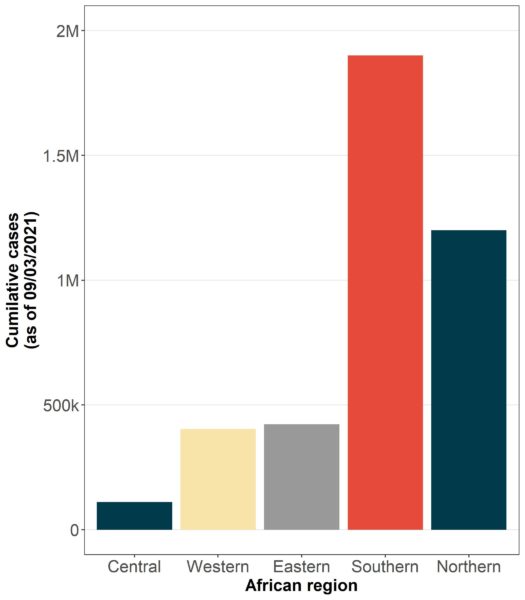

However, significantly lower rates of infection (and associated mortality) were subsequently seen in the equatorial belt comprising West, Central and Eastern Regions (as defined by the African CDC), illustrated in figure 1 [2].

While the reasons for this remain unclear, it raised the issue of the balance of benefit and harm arising from cessation of health targeted programmes. For NTDs there was the risk of policies aimed at reducing COVID-19 infections instead resulting in increased NTD transmission and associated morbidity and mortality. There was also the risk of lost traction in achievements towards the WHO NTD 2030 elimination goals [3].

Throughout the pandemic, ministries of health have been the primary decision-makers responsible for ceasing, continuing, and restarting NTD programmes in their respective countries. As the nature of the pandemic became clear and once the initial preparedness and outbreak responses in countries were defined and set-up, ministries expressed interest in restarting their NTD programmes.

However, reinstating NTD programmes meant Ascend country leads needed to understand key blockages to programming resulting from COVID-19 policies, such as school closures and travel restrictions, that would need to be adapted to before resuming activities. This was made possible through ongoing collaboration with partner governments and WHO country offices, with the Ascend team then working to ensure the health and safety of those involved in programme delivery and those receiving NTD services financed with FCDO funding, while supporting partner government decision-making and, ultimately, implementation of an adapted NTD programme.

All NTD related activities currently undergo a stepwise review, identifying appropriate mitigating strategies with the aim of minimising the risk of COVID-19 transmission associated with programme delivery.

The response also requires accounting for:

- The distribution of the individual NTDs among a population

- The current rates of COVID-19 transmission in the target areas, and ability of the health system to withstand an outbreak

- The clinical and population impact of pausing the programme.

- The type of NTD intervention – such as one-to-one contacts for trachoma surgery or one-to-many contacts for Mass Drug Administration (MDA).

- Perception of risk by ministries of health

- Real, presumed and expected community responses

- Assessing risk among people the programme is responsible for

Whilst there was, and is, a varied response by country, there were commonalities in the adjustments made to NTD programmes as part of ensuring continued safety in delivery (Box 1).

Box 1: Common adjustments required to restart NTD programming

- Amended standard operating procedures (SOPs) ensuring precautions taking into account government and local restrictions. For example:

- School closures required amended MDA delivery

- Adjustment to house-to-house distribution as opposed to central community distribution points

- Amended training delivery

- to allow for social distancing – this included smaller training group sizes and avoiding travel

- adjusting training content to include COVID-19 amended delivery and safety precautions

- Understanding community acceptability of activities during the pandemic, and ensuring staff safety

- Amending social mobilisation as well as Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials, to increase community engagement and ensure COVID-19 messages and adjustments are known

- Additional staff, time and accommodation for increased planning, distribution and monitoring requirements

- Provision of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face masks and hand sanitisers for health staff

- Additional vehicles to account for greater staff requirements and distribution points to avoid crowding

- Remote supervision strategies where possible

- Providing personal protective equipment (PPE) and hand sanitising equipment

An ongoing concern is the perceived acceptability of NTD interventions by communities in light of COVID-19. Anticipated challenges varied from a general hostility to healthcare workers arising from the closure of health facilities, to concern that health workers might spread the disease. The extent of ongoing community acceptance remains to be seen, but an encouraging factor is that recent research shows lower acceptance of conspiracy theories in low and middle-income countries than in high-income countries [4].

The most significant impact of COVID-19 adaptations to NTD programme delivery was on human resources (Box 2), requiring either additional staff, or enabling existing staff to take longer than planned to deliver interventions.

Box 2: Factors behind staffing restrictions for implementation of NTD programmes during COVID-19

- Redirection to Covid-19 response.

- Additional training and time for training to include COVID-19 precautions.

- Diversion to (essential) co-ordination with national and local authorities.

- Community engagement taking either longer or needing more staff.

- Amended house-to-house delivery for MDA requiring additional staff time to target.

-

Assessing and managing risk during the pandemic

Earlier in the pandemic, risk assessment was a major activity. A Risk assessment and mitigating activity tool (RAMA) was developed to enable the Ascend programme and partner ministries to have an up-to-date overview of the degree of risk posed by reinitiating programmes in each country. The tool weighs the risk of onward transmission of COVID-19 against processes in place to mitigate against transmission risk and the programmatic risk of a sub-optimal NTD control programme.

The RAMA tool was developed by SightSavers, based on a WHO tool [5,6,7], with inputs from NTD partners including Ascend lot 1.

In general, the tool was welcomed by partner countries and proved essential in not only making decisions on continuing, restarting or stopping NTD programmes, but also identifying all programmatic stages which required risk assessment and mitigation. Some issues remain as to how the tool can be used to monitor a dynamic situation of fluctuating transmission rates.

- Benefits emerging from country responses

Whilst COVID-19 has had significant adverse effects globally, country teams also report benefits from their country’s respective national responses to the pandemic (Box 3).

Box 3: Key benefits from country responses

- Increased national resilience and public health capacity.

- Enhanced relations and communication with: Ministries of Health, other Ministries, and local/regional governments.

- Introduction of new technologies.

- Increased public awareness of hand hygiene

In addition, some countries have started developing their own PPE manufacturing capability and there has been greater adaptation to technology, with virtual meetings and training and the use of mobile applications to provide remote patient management becoming commonplace.

In respect of the NTD programme, the outbreak has led to:

- Improved contact and co-operation with other MoH departments, as well as other ministries (such as water and education), allowing NTD departments to work collaboratively across sectors.

- Improved hand hygiene, with the focus on messaging around hygiene and hand washing with soap to protect against COVID-19 likely to have a beneficial impact on a variety of NTDs, including schistosomiasis and trachoma.

- Improved relations with individual states/regions, leading to a better understanding of the cultural diversity in countries comprised of many separate groups. This will help improve health promotion activities.

- An uncertain future

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve and the overall impact on NTD programmes in terms of cost, effectiveness and timeline for elimination remains uncertain.

The role and impact of COVID-19 immunization is unclear and will be a major factor in determining future NTD rollout. Vaccination programmes will require significant resources, which may impact adversely on the timeline for NTD elimination by diverting resources to these programmes. The community-based system set up to deliver the NTD programme might also be utilised to speed up the immunization programme, but this needs consideration [7].

The eventual cost of the COVID-19 pandemic on NTD elimination goals will also need to be quantified and assessed. There will undoubtedly be an impact upon the programme, but it is as yet too early to assess the extent of COVID-19, not just on NTDs but also upon other aspects of healthcare.

With the pandemic ongoing in the region and likely to continue for some time, we can anticipate that COVID-19, and the need for continued mitigation against the threat of transmission in Ascend countries will remain for the foreseeable future. Short term outbreak responses will need to shift gears to instead become embedded standard processes for health care delivery. Similarly, the health sector needs to reflect on learnings from the current pandemic response to prepare for future outbreaks.

References

[1] COVID-19: WHO issues interim guidance for implementation of NTD programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/news/COVID19-WHO-interim-guidance-implementation-NTD-programmes/en/

[2] Africa CDC https://africacdc.org/covid-19/ accessed 28 Jan 2021

[3] WHO | Ending the neglect to attain the Sustainable Development Goals: A road map for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030 accessed 26 Jan 2021

[4] Anti-vaccination sentiments are more prevalent in rich countries than in poor ones; https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2020/08/29/conspiracy-theories-about-covid-19-vaccines-may-prevent-herd-immunity accessed 27 Jan 2020

[5] Community-based health care, including outreach and campaigns, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; May 2020 accessed at Community-based health care, including outreach and campaigns, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic (who.int)

[6] WHO mass gathering COVID-19 risk assessment tool – Generic events, July 2020 accessed at WHO mass gathering COVID-19 risk assessment tool – Generic events

[7] Molyneux D. et al. Infectious Diseases of Poverty, 2021

The UKAid funded Ascend programme in Nepal (Lot 1) is managed by a consortium of Crown Agents, Oriole Global Health, ABT Associates and KIT Tropical Institute