Re-directing existing spend on diesel generators at health facilities towards the provision of solar energy is not only good for the climate – it makes financial sense.

Re-directing existing spend on diesel generators at health facilities towards the provision of solar energy is not only good for the climate – it makes financial sense.

Less than half the people living in sub-Saharan Africa – and just 28% of rural dwellers – have access to electricity, making this the world’s most electricity deprived region. In countries where grid power is available, reliability is often poor, with frequent and extended power outages a part of everyday life.

Energy poverty remains one of the sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest developmental challenges, with significant impacts on peoples’ health and quality of life.

Where health clinics and hospitals lack adequate electricity, vaccines cannot be refrigerated, medical equipment cannot be sterilised, emergency night-time medical care must happen by torch-light, and medical record keeping is poor. These effects of poor energy access are linked to noticeably higher maternal and child mortality and significant challenges in attracting and retaining qualified medical staff.

To close this electricity access gap, many health facilities end up using diesel-powered generators either as a sole source of electricity, or as back-up during grid power outages.

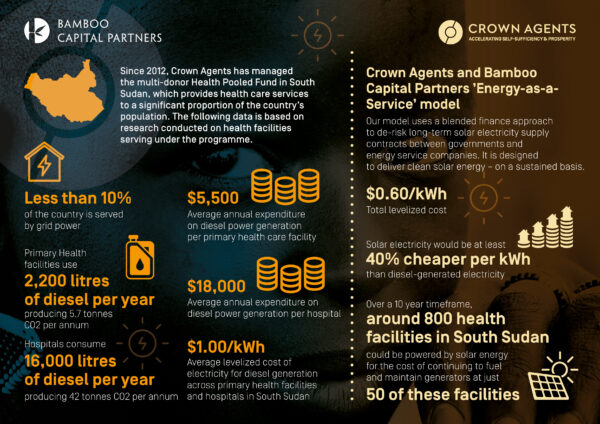

In South Sudan, less than 10% of the country is served by grid power. As a result, all hospitals and a significant number of primary health care facilities rely heavily on diesel-powered generators. Using data from the South Sudan Health Pooled Fund Programme – a multi-donor Crown Agents managed initiative delivering health care services to a significant proportion of the country’s population – we estimate diesel generators at primary health facilities use around 2,200 litres of diesel each year (each producing 5.7 tonnes CO2/annum), and hospitals around 16,000 litres per year (each producing 42 tonnes CO2/annum).

Diesel generators are expensive to run and maintain. For the health facilities operating in South Sudan, the average annual cost of diesel generator power in 2021-22 was $5,500 per primary health care facility, and upwards of $18,000 per hospital. This amounted to an electricity cost of between $1.00/kWh and $1.33/kWh. Fluctuations in the price and availability of diesel are additional wild cards that can systematically drive up costs, or comprise energy provision altogether. In response to recent spikes in diesel prices, some health facilities are starting to reduce daily generator run times, which in turn impacts on the number of patients being treated.

Where money is being spent on diesel generators to power health facilities, there is an obvious opportunity for positive change. This money could instead be spent on clean, reliable, renewable energy.

Decentralised solar energy systems have progressively improved in efficiency and price over the past few years. Modular designs allow for rapid deployment and incremental scale-up to meet changes in demand at individual health facilities. We estimate that switching from diesel generators to solar energy at hospitals and health facilities in South Sudan could reduce the cost of electricity by at least 40%, to around $0.60/kWh.

For countries like South Sudan, which has one of the lowest health care budgets in the world, making savings through using solar power instead of diesel generators could mean more health facilities get electricity, and more lives being saved.

This idea is not new. However, finding a sustainable solution to solar electrification of publicly-owned health facilities has been a significant challenge. Over the past few years, donor funded health facility electrification programmes have tended to only cover the up-front costs of solar installations, but failed to make long term provisions for operation and maintenance costs. These programmes have often failed to incentivise stakeholders, including governments and the private sector, to ensure reliable provision of electricity supply to health facilities over the long term. This has led to a proliferation of defunct solar energy systems at health facilities across sub-Saharan Africa.

Crown Agents and Bamboo Capital Partners have joined forces to develop an “energy as a service” model, which facilitates cost efficient, sustainable supplies of solar electricity to public facilities – including health facilities – at significant scale in low and middle income countries.

Our model – named Solar4Health – uses a blended finance approach to de-risk long-term solar electricity supply contracts between governments and energy service companies, which then install, operate and maintain solar equipment at health facilities. By pooling government budgetary contributions, donor funding and private capital, energy service companies are provided access to concessionary loan finance as well as guaranteed payments for solar electricity provided under contract to government. Through this arrangement, energy service companies ensure the provision of high-quality, reliable electricity to health facilities for the full 10–15-year contract period.

We believe that by deploying Solar4Health as a robust, de-risked “energy as a service” model, significant commercial capital can be attracted. This will multiply the impact of donor funding and facilitate health facility electrification to scale from the few thousand facilities electrified over the past 5 years to reach the 100,000 facilities in sub-Saharan Africa that still lack access to reliable electricity.

Based on our model, we project that, over a 10-year timeframe, the majority of health facilities (close to 800) in South Sudan could be equipped with whole-facility solar power for almost the same cost as continuing to operate diesel generators at just 50 of these facilities over the same period.

Private capital is reluctant to invest long-term in health facility electrification because of the payment risk from government. Our model offers a mechanism to leverage donor funds – which would otherwise have continued to fund dirty energy – to attract private capital and replace diesel generators at health facilities as well as electrify facilities that currently have no access to power.

By creating attractive conditions for private capital investment, our model also seeks to accelerate the delivery of solar energy at public facilities beyond that which could be possible through grant and philanthropic funding alone.

The financial case for making the switch is an obvious one – particularly to ensure that countries like South Sudan not only have improved access to renewable energy, but are able to do more with less, and, as a result, save more lives.